When Steven Spielberg grew up in the postwar era, stories of gun-slinging cowboys fighting Native Americans were extremely popular because they represented the way America wanted to be seen at the time, as a strong and heroic wielder of justice. He snuck in to see John Ford’s “The Searchers” when he was nine years old (via The Hollywood Reporter). It became not only one of his favorite films, but also one of his greatest artistic inspirations.

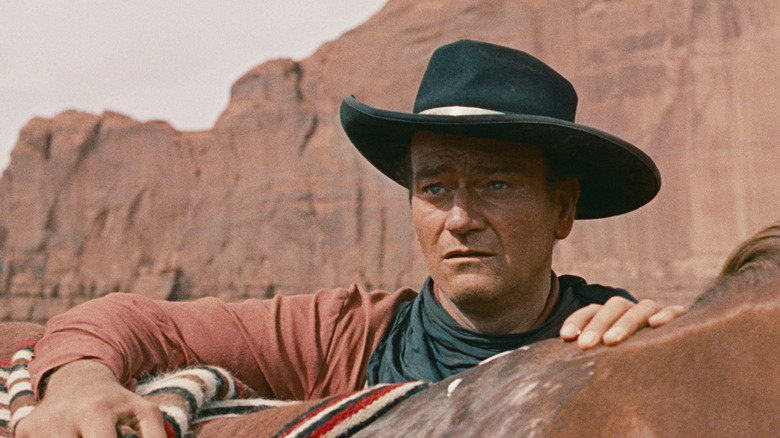

Often considered the best Western of all time, “The Searchers” defined the genre’s tropes we all know and love. John Wayne delivers his best performnce as Ethan Edwards, a Civil War veteran who goes on a five-year search for his nieces who were kidnapped by the Comanche after tribe members burned down his homestead and killed his brother, sister-in-law, and their son. “The Searchers” has all the spectacle and adventurous excitement we’d later see in Spielberg’s “Indiana Jones” series, but its deeper themes of home and family resonated most with him and are embedded in nearly all of his films. Ethan sees home as somewhere he can feel safe and in control. Without his family there, Ethan is even more rattled by the violence after the recent war.

Despite operating in entirely different genres, this yearning for stability and feeling of being left behind appears in Spielberg movies like “E.T.,” where Elliot desperately wishes E.T. could be part of his family instead of going back to space, or “Artificial Intelligence,” where the robot child David relives the memory of his happiest day: Simply being with his mother inside their brightly lit home. These homes are broken, but the protagonists want to put them back together.

Spielberg was not only emotionally connected to “The Searchers,” but it also taught him a very important lesson about filmmaking.

Director John Ford taught Steven Spielberg how to paint with a movie camera

Steven Spielberg told AFI that he watches John Ford’s filmography, especially “The Searchers,” for inspiration before he makes his own movies:

“I’m very sensitive to the way he uses his camera to paint his pictures and the way he frames things. And the way he stages and blocks his people, often keeping the camera static while people give you the illusion there’s a lot more kinetic movement occurring when there’s not. In that sense, he is like a classic painter. He celebrates the frame, not just what happens inside of it.”

Spielberg met John Ford when he was a teenager, which he recounts in his semi-autobiographical “The Fabelmans.” Ford is played by another visionary filmmaker, the late David Lynch, in a poignant and perfect final onscreen performance. The cantankerous and chain-smoking Ford describes the importance of not simply putting the horizon line in the middle of the frame, but rather pushing it closer to the top or bottom to generate a more compelling image. We see these painterly techniques throughout “The Searchers,” especially in the haunting final shot where Ethan stands cloaked in shadow and framed by a doorway, looking out onto the vast plains where he no longer belongs.

John Ford’s most famous Western showed Steven Spielberg how to intentionally craft shots with emotional and visual grandeur that make use of every corner of the frame. Spielberg learned how to be a visually expressive filmmaker by repeatedly studying his favorite movie, and now he’s produced some of the most iconic images in cinematic history, including looking up at the swimmer’s legs in “Jaws”, the T. rex roaring as the banner falls in the original “Jurassic Park,” and the silhouette of E.T. soaring across the moon, among countless others.